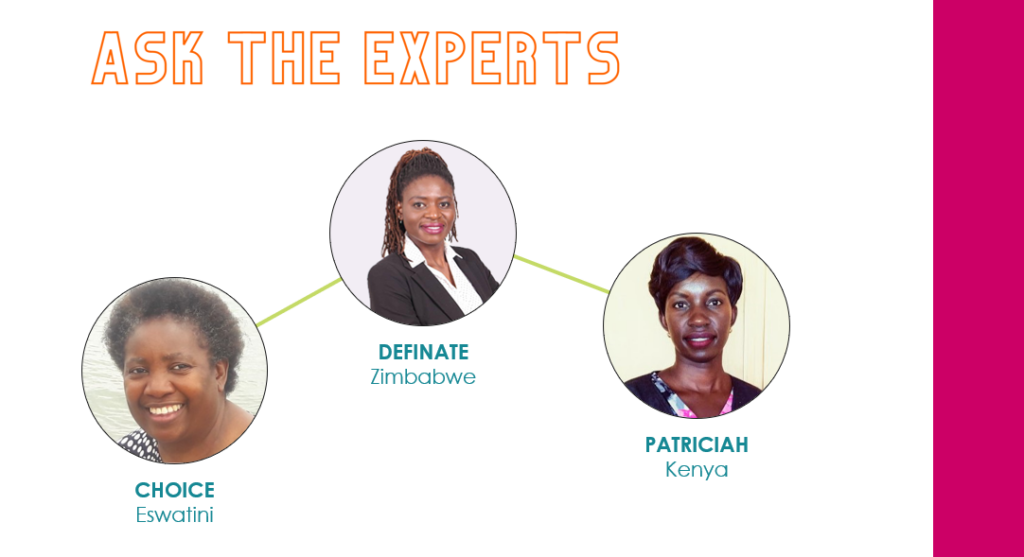

Definate Nhamo, Senior Programs Manager, Pangaea Zimbabwe AIDS Trust (PZAT)

In 2004, my experience as a trainer began. I started off as a life skills and comprehensive sexuality education trainer. Over time, I trained groups in financial literacy, economic livelihoods, HIV prevention, and advocacy, to name a few. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, I had always conducted trainings in person. So, it was quite the change to move to an entirely virtual format for the HIV Prevention Ambassador Trainers’ Workshop. Now, after our third iteration, I have reflected on the differences between in-person and virtual trainings as well as the adjustments we have had to make along the way.

When conducting in-person trainings, I am able to check for understanding through nonverbal cues like smiling faces, relaxed expressions, and the nodding of heads. All of this falls away when conducting trainings in a virtual environment, creating a major challenge.

Virtual trainings are marked by unstable connectivity, participants falling out of the training and re-joining as they are able, and distractions that lead to multitasking and use of training time to engage in other work-related activities without the trainers’ knowledge.

Virtual trainings, therefore, require a lot of assumptions—trust being foremost. As a trainer, I assume that participants are tuned in, listening, and following along with the material. This is a huge assumption we make as trainers because sometimes participants will log into the training and then leave the room to conduct other work. My experience with virtual training has taught me to always check in with participants and involve them often to ensure that they are paying attention.

During the HIV Prevention Ambassador Trainers’ Workshop, we incorporate collaborative activities as much as possible, with participants expected to give input and actively contribute to team learning in real time. This ensures that everyone in the group is present, and if someone needs to step away, they feel compelled to notify us just as they would during an in-person event. Asking participants questions is also crucial, as it helps us to check who is engaged and who is not.

We incorporate several interactive components into our workshop curricula to ensure engagement among participants. Participants are tasked with preparing their own role plays and teach-back sessions, which is one sure way to keep them highly involved. During the live virtual sessions, participants are also placed in small groups and matched with a mentor and they meet together at the end of each day to touch base and complete assignments. In the small groups, there is opportunity for real connection. Mentors check in with their mentees and ask them how the session went, what worked and what did not, and what they would like more of in future sessions. These check-ins at the end of the day have helped us assess the level of participant engagement and make sure everyone is up to speed and feeling confident about the material.

Fun is also important. We include fun-filled content checks, quizzes and polls, and games in our sessions. These additions are critical in virtual trainings because they compel participants to pay attention to the content and interact with the material as it is delivered.

In summary, virtual trainings can be a good way to continue learning while we live and work in this new normal. We must consider the checks and balances in place to guarantee we achieve what we set out to do: real, sustainable learning and skills building. In the absence of adequate checks, virtual trainings can result in less-engaged participants using the time to multitask and missing the objective. Through our HIV Prevention Ambassador Trainers’ Workshop, we—the trainers—have learned a lot about how to keep participants actively engaged, which has resulted in continuous improvements to the training itself. Although we always have more to learn, we now feel confident in our ability to conduct effective trainings in a virtual world.

This is the second blog post in a series on the design, development, implementation, and iterative processes of the interactive and virtual HIV Prevention Ambassador Trainers’ Workshop, led by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)- and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-supported Collaborative for HIV Prevention Options to Control the Epidemic (CHOICE) through the terms of cooperative agreements of the EpiC and RISE projects. In this series, we share our experience and reflect honestly on the ups and downs of designing and delivering a comprehensive training virtually. Access the HIV Prevention Ambassador Trainers’ Workshop materials here.

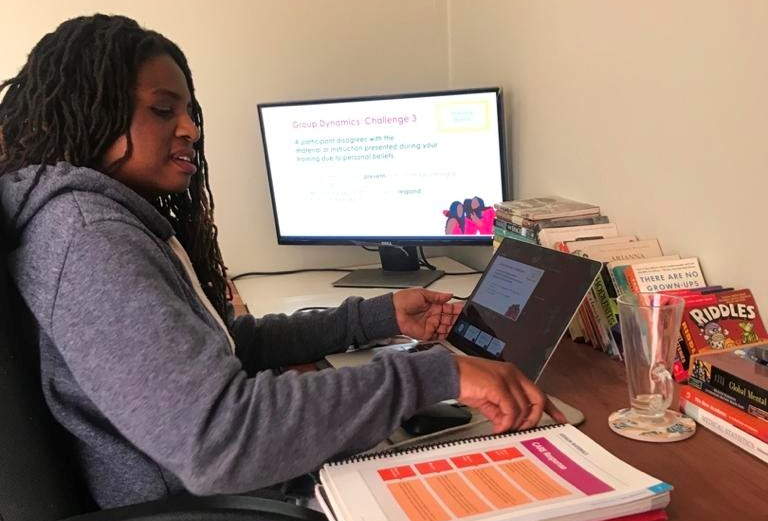

Photo Credit: PZAT