Written by LINKAGES’ Hally Mahler, Eric Stephan, Matthew Avery, and Virupax Ranebennur

A version of this blog post was originally presented at FHI 360’s Global Leadership Meeting 2017 and USAID’s Global Health Mini-University 2017.

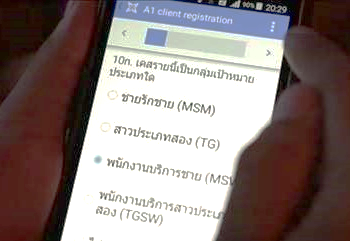

Photos courtesy of Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Center.

Read Part I and Part 2 of this three-part blog series here.

Motivated by the success we had in Chiang Mai, the LINKAGES team set out to find if similar social network approaches could be applied to men who have sex with men (MSM) in India – where 90 percent of MSM in Mumbai use virtual spaces to seek sexual partnerships.

Within the first three weeks of the pilot, mobilizers were able to reach 333 MSM who solicit sexual relationships through social apps, 93 of whom sought prevention, care, and treatment services including HIV testing. Almost all of these MSM individuals were university students that were not being reached through traditional, targeted intervention programs. As a result of the pilot’s success in utilizing social networks, the team observed an HIV yield increase from 1 percent to 4.1 percent, and a 9 percent syphilis yield. What did the data tell us? This group of young men were a previously unreachable priority population with a significantly high risk of HIV.

Expanding out of Asia

Currently, LINKAGES has expanded implementation efforts of the Enhanced Peer Mobilizer (EPM) model in five countries in Africa – Botswana, Burundi, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Malawi. These new experiences have taught us lessons about how social networks work in different contexts.

In Botswana, LINKAGES is working exclusively with female sex workers (FSWs). In November 2016, we designed a pilot strategy based on the EPM model in an effort to reach FSWs online. Within the first four weeks, we tested 1,665 FSWs compared to the 951 FSWs reached in the previous quarter. An analysis of one district in Francistown revealed that 282 FSWs were brought in for HIV testing by only three super-mobilizers; 93 percent of those were first time users of LINKAGES’ HIV services. The HIV case finding increased from 13 percent at the start of the pilot to 31 percent. The deeper we got into the social networks, the more HIV-positive sex workers we found and linked to care.

LINKAGES discovered a similar trend in Burundi, where there was a large increase in case finding reported from all implementing partners, both in urban and rural areas. We then took the approach to MSM groups in Cote d’Ivoire and Malawi, and again in both cases we saw improvements in HIV case finding. The proof of concept is strong, but the challenge we now face is getting the approach to scale. LINKAGES achieved what is now called the Enhanced Peer Outreach Approach (EPOA) in Thailand and learned many lessons along the way that will inform our plans to scale up elsewhere.

What we have learned

- The Enhanced Peer Outreach Approach has the power to reach previously unreached – and sometimes unknown – networks of MSM and FSWs.

- From this early view, MSM and FSW networks may tend to look different. MSM networks usually have a single individual surrounded by many contacts, whereas FSW networks tend to present in waves and branches. The higher use of social media by MSM individuals may contribute to this.

- High levels of social media use by targeted key populations is beneficial for scale but not essential for success.

- HIV-positive mobilizers tend to bring in a higher percentage of HIV case finding.

- The longer the strings, the more HIV case finding for FSWs and some MSM groups – especially where social media is not used. We see higher yields come in around the third and fourth waves when we are reaching people not previously reached by the project.

- It is imperative to seek mobilizers with social networks outside of the groups we are already reaching through other methods. We had a few cases in which the coupons never left the community who were already being reached by traditional program interventions, thus resulting in no additional case finding.

Considerations for the future of the Enhanced Peer Outreach Approach

- Incentives have been important to the success of the program – be they direct payment or in-kind incentives. It is important for any incentives to be tailored to the country context in consultation with the KP groups that will be reached by the program.

- The use of mobilizers does not replace more traditional peer outreach workers! We still need outreach workers to maintain contact with new clients once they have been found. We are pursuing questions about how to keep mobilizers motivated, and how to further expand program promotion once personal social networks have been exhausted.

- Since the Enhanced Peer Outreach Approach brings in people who have never had contact with the program previously, it may be harder to effectively link them to care and treatment and continue to support them in the community.

You are who you know

There is still so much to be done, and we suspect that – when it comes to social networks, super-mobilizers, and sex – we have just reached the tip of the iceberg in our learning. What we do know is this: online social networks have dealt a substantial blow to the way a number of industries have worked for decades, including the news, television, job-hunting, shopping, and entertainment. These industries have been disrupted and recreated with online tools and spaces, and the same holds true for LINKAGES’ work. In Thailand and India, we saw people in online social spaces take on the task of referring their peers to HIV services themselves, in much the same way that young people now become salespeople or social media stars (i.e. “Instagram-famous”) due to their own personal branding.

As we saw in Botswana, even without a strong social media presence, key population communities around the world can harness their social power, through their own networks to become gatekeepers for HIV education, outreach, referrals, and even care and treatment. In an ever-changing online and off-line landscape, we believe this is a positive development. It will require us to continuously evolve, but innovation is both inevitable and necessary for progress. And, in the end, you truly are who you know, and who you know can make all the difference in bringing an end to HIV.