Written by LINKAGES’ Hally Mahler, Eric Stephan, Matthew Avery, and Virupax Ranebennur

A version of this blog post was originally presented at FHI 360’s Global Leadership Meeting 2017 and USAID’s Global Health Mini-University 2017.

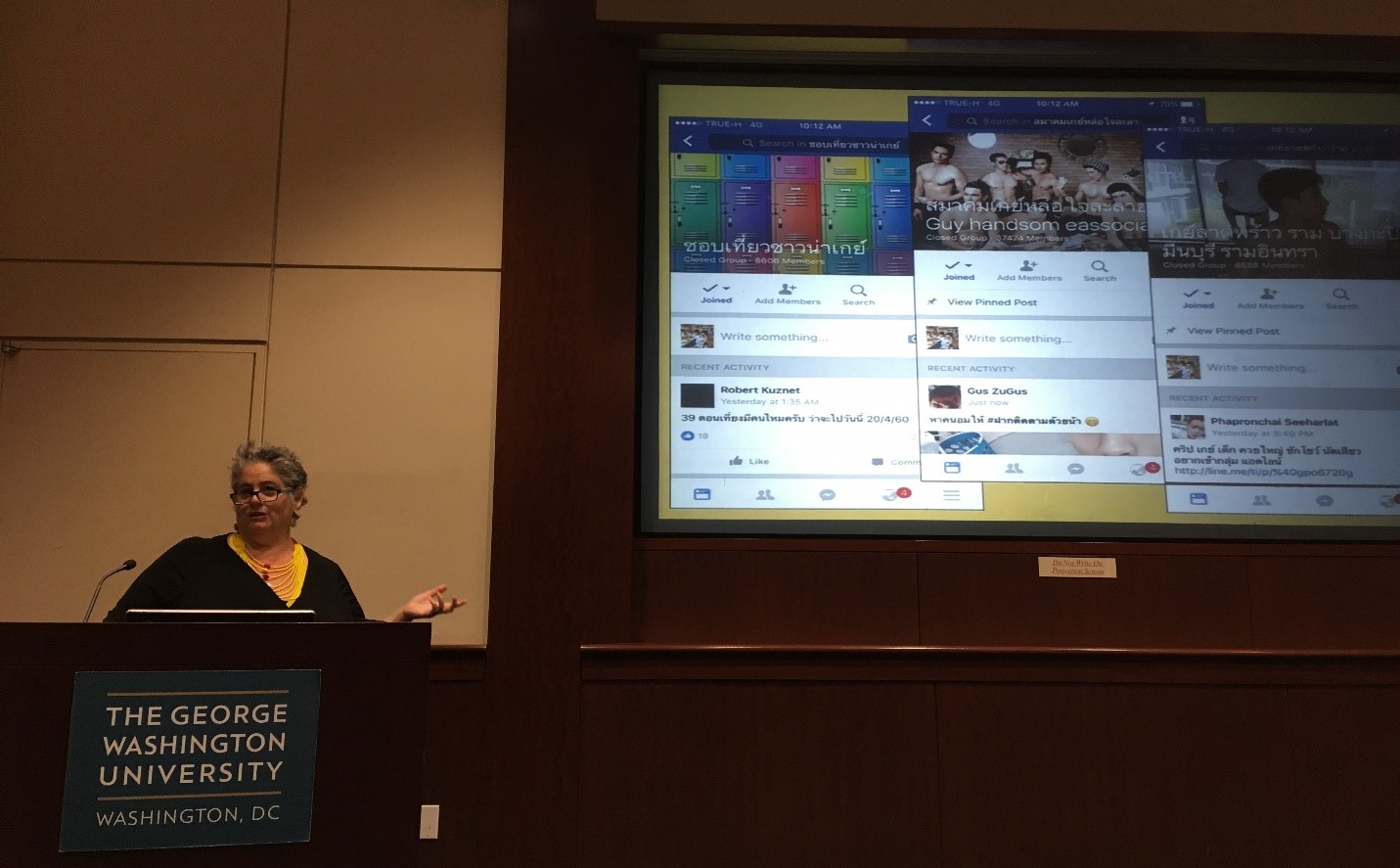

LINKAGES Director Hally Mahler presents at USAID’s Mini-University on September 14, 2017.

The USAID– and PEPFAR-funded LINKAGES project partners with communities, governments, and the private sector in 30 countries around the world. Our goal is to deliver HIV prevention, care, and treatment services and address essential cross-cutting issues such as the capacity building of key population (KP) led community organizations, stigma and discrimination, access to and delivery of dignified health care, and violence prevention and response. At the country and global levels, we also work with the World Health Organization, Global Fund, and others to strengthen data and cascades and improve the technical quality of key population programming.

LINKAGES’ team spends a lot of time asking, how can we implement just the right combination of interventions to make a big impact on the HIV epidemic – to achieve the “holy grail” of epidemic control?

We used to think that to fight HIV, it was up to our projects to mobilize outreach workers and maximize “reach” through our own legwork. But increasingly, and maybe obviously, what we are discovering is that the people who will bring an end to HIV and AIDS are not exactly “us” but the people in our social networks. They are our friends, our partners, and our support groups. Through social media technology, our networks become empowered.

MSM in Chiang Mai, Thailand

Chiang Mai is a popular city in northern Thailand with thriving KP communities. In recent years, Chiang Mai has made incredible progress in the fight to end HIV. However, rates of new HIV infections continue to be disproportionately high for MSM and transgender women and, in 2014, less than 20 percent of HIV-positive MSM in Thailand were aware of their status. Of those who were aware, only 1/3 were adhering to a treatment regimen.

In Thailand and most other countries around the world, these KP groups have a higher risk for HIV infection and they are less likely to receive preventative services or care and treatment if they are HIV-positive. This is especially troubling, as the AIDS Epidemic Model estimates that 53 percent of new HIV infections from 2015-2019 will result from male-male sex.

LINKAGES’ response

In 2015, we asked ourselves, how can we reach more MSM with HIV programming, and especially those who have not been reached before?

Since traditional methods have typically resulted in about 1/3 of reached clients electing to receive an HIV test, LINKAGES began to think outside the box. How can we improve uptake of testing and HIV case findings in these communities? We decided to shift the responsibility for recruiting new clients onto the program clients themselves. This was inspired by respondent-driven sampling methodology used in research, where study participants are given coupons to pass onto their friends and others in their social circles; those making successful referrals are awarded a small cash incentive.

With respondent-driven sampling, we are usually interested in a representative sample. However, our assumption here was that people who are highly vulnerable to HIV themselves usually “run” or associate with other vulnerable people. These are also the groups least likely to be reached by our usual program activities. To reach these communities, the LINKAGES Thailand team started using eCascade, a smartphone app that collects data in real time and guides outreach workers with questions to ask potential clients and steps to take to link individuals to care. We added a component to eCascade prompting outreach workers to offer their clients coupons that they could use to recruit new individuals into the program: “We’re so glad to have this talk with you. If you take 3 of these coded coupons and give them to your friends, and a friend brings the coupon back to me to have a talk and referral to testing, then you will earn 100 baht for having brought us a new client.”

Clients who agreed to distribute these coupons became peer mobilizers and we named our strategy the “Enhanced Peer Mobilizer” (EPM) model. Like with respondent-driven sampling, when coupons come back to us with a new client, and then that new client distributes coupons to bring in the next wave of friends, we can use the unique coupon codes to create a visualization of social network nodes.

The development of “super-recruiters”

This type of social network analysis used to take days, but with more modern tools we are now able to visualize social network recruitment in real time. These networks give us a wealth of knowledge. They can tell us in which social networks HIV-positive MSM and transgender women are found, which networks have more first-time testers, and who the most valuable and successful recruiters are.

Why do we want to know all of this? Once we identify which networks produce priority clients, our community partners – including Caremat, which manages a large cadre of known HIV-positive clients who receive ongoing care and support – can then “pivot” to work intensively with those individuals to maximize recruitment and HIV testing successes.

When we first launched these efforts back in 2015, we started to notice an interesting pattern of networking in Chiang Mai. When we visualized our early social networks, we saw, right in the middle of the social networks display, a huge round cluster surrounding one particular peer mobilizer. With two months of work completed under our EPM model, our best peer mobilizers had brought in 10 new contacts each. But one individual had brought in 71 clients alone, and he was just getting started.

Stay tuned for Part II of “You are who you know: Social networks, super-mobilizers, and sex.”