Written by Aubrey Weber, Technical Officer, FHI 360; Emily Evens, Scientist, FHI 360; & Michele Lanham, Technical Officer, FHI 360

This blog post was first featured on FHI 360’s R&E Search for Evidence website.

GBV study data collectors from Trinidad and Tobago (Photo: FHI 360)

Female sex workers, gay men and other men who have sex with men, and transgender (trans) women – collectively referred to as key populations (KPs) – are disproportionately affected by HIV and violence, including gender-based violence (GBV). GBV refers to any form of violence that is directed at an individual based on biological sex, gender identity or expression, or perceived adherence to socially-defined expectations of what it means to be a man or woman, boy or girl. GBV against KPs is prevalent, frequent and often severe in Latin America and the Caribbean, and a growing body of literature links experiences of GBV to increased HIV vulnerability and reduced access to HIV services.

Yet, we know little about the types and consequences of GBV in KP members’ lives, if they tell others about violence and whom they choose to tell, and what support they seek following violence. An additional gap is understanding how HIV programs can be more responsive to KP clients who have experienced violence. Our research team’s new article in a special issue of BMC International Health and Human Rights can begin to fill this evidence gap.

In this post, we outline our study methods and findings presented in the article, “Gender-based violence among key populations in Latin America and the Caribbean: A qualitative analysis to inform HIV programming.” Our study is led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the LINKAGES project.

Participatory, rights-based research methods

In 2016, together with The University of the West Indies (UWI) and UNDP, our team of LINKAGES researchers collected quantitative and qualitative data on experiences of GBV among female sex workers, men who have sex with men, and trans women in Barbados, El Salvador, Haiti, and Trinidad and Tobago through structured one-on-one interviews.

Our study participants (n = 278; 119 female sex workers, 85 men who have sex with men, 74 trans women) were recruited from KP-focused civil society organizations. All participants gave informed oral consent before being interviewed.

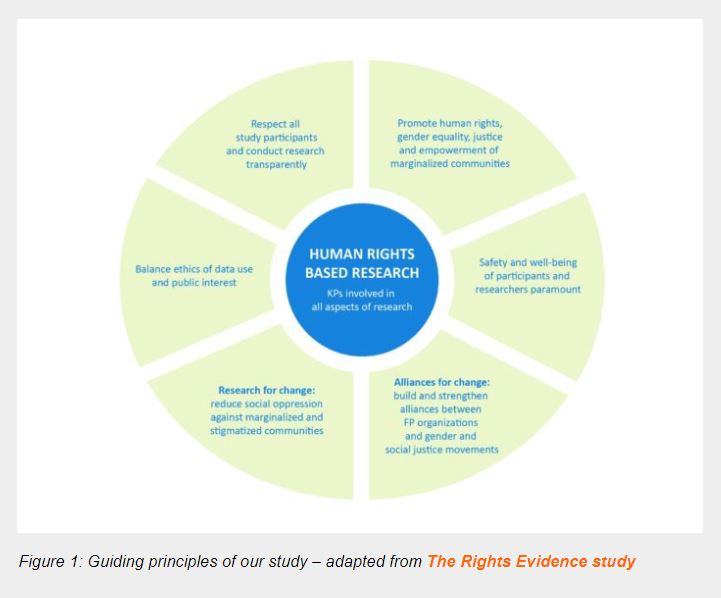

Using principles of participatory, human rights-based research (Figure 1), members of the KP groups contributed to designing our study, identifying interview topics, developing interview guides, selecting sites, recruiting participants, ensuring the safety of data collectors and participants, conducting interviews, and interpreting results. Our study received human subjects research ethics approval from the FHI 360 institutional review board and local ethical review committees.

Female sex workers, men who have sex with men, and trans women conducted all data collection. Our local researchers supported and trained them in qualitative research, interviewing skills, speaking to victims of violence, study procedures and research ethics.

Our team formed regional and national advisory groups, which included civil society organizations working with KPs, United Nations agencies, USAID, UWI and government representatives. The advisory groups promoted collaboration between government and civil society groups and ensured they were ready to translate study results into concrete actions. The advisory groups also provided guidance on the questions we asked study participants and the procedures used for collecting data.

Our study team developed structured interview guides covering experiences of GBV in a variety of settings and included a list of close-ended questions about participants’ specific experience and open-ended questions on what consequences violence had on them, to whom they disclosed GBV, what services they sought, and what types of support they wanted to receive.

Our team entered responses to closed-ended questions using EpiData with double data entry for accuracy, exported the data to STATA, and then analyzed it descriptively by KP group and study site. We transcribed, translated and coded responses to open-ended questions using QSR NVivo in the cases of Barbados, El Salvador, and Trinidad and Tobago, and using a structural matrix in the case of Haiti since those interviews were shorter and less detailed. Our team then jointly coded transcripts until they achieved intercoder reliability. We periodically assessed intercoder reliability thereafter. We then looked at all the text assigned to each code and organized it into themes with supporting quotes.

After data collection and preliminary analysis, our study team held interpretation meetings in each country to review the data, ensure accuracy of interpretation, prioritize results, and discuss the dissemination plans. Following individual country analysis and interpretation meetings, our team then merged and summarized the data across countries.

Results

Experiences of GBV

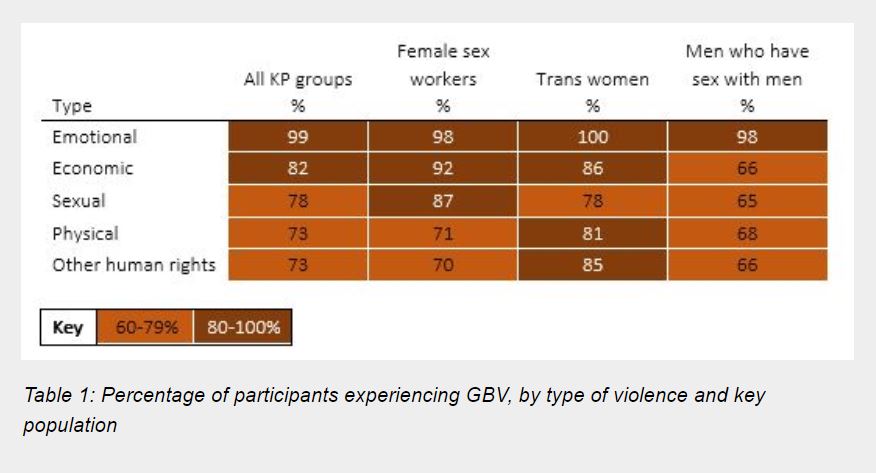

All KP groups across our study sites reported experiencing some form of violence. You can find the full breakdown of the quantitative data in Table 1 below.

Nearly all study participants (99%) reported experiencing emotional GBV, e.g., psychological and verbal abuse, threats, coercion and bullying. Over 80% of all participants reported experiencing economic GBV, including using access to money or resources to control individuals, blackmail, refusing individuals the right to work, or taking their earnings.

Trans women reported the highest percentage (81%) of physical violence experiences, e.g., kidnapping, being forced to consume drugs or alcohol, while female sex workers reported the highest percentage (87%) of sexual violence, e.g., rape, coercion or intimidation to engage in sexual activity against one’s will, and refusal to wear a condom.

Trans women also report the highest percentage (85%) of other human rights violations, such as denial of basic necessities, arbitrary detention, or arrest and denial of health care, education or access to identity documents. You can learn more about findings related to trans women in a previous blog post.

Settings where GBV occurs and perpetrators

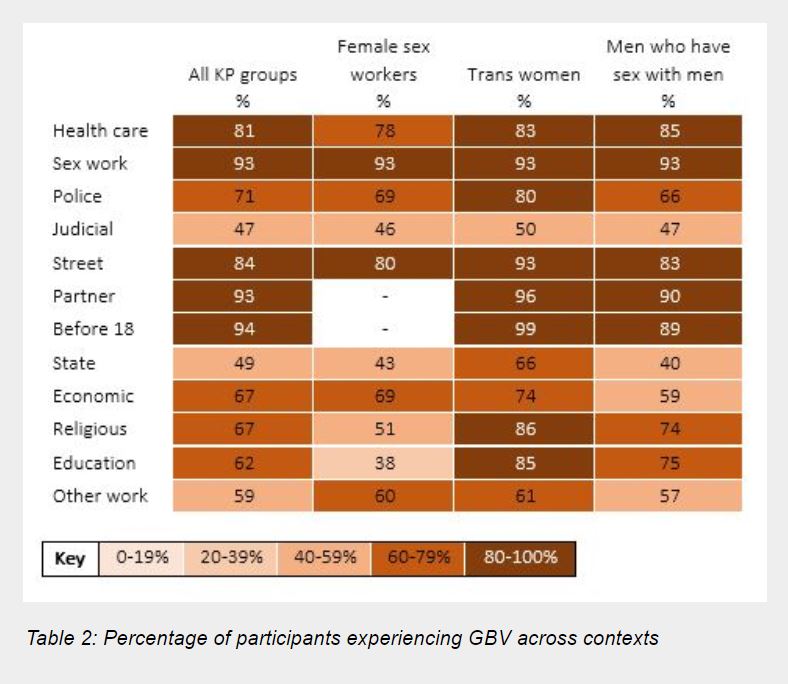

Our study participants also reported that GBV occurred in a range of contexts and throughout their lives. You can find a full breakdown of the quantitative data in Table 2 below.

The most common settings for GBV across all participants and study sites were violence in a sex work setting (93%), violence in a health care setting (81%), and violence in the street or other public spaces (84%). Most men who have sex with men (~75%) and trans women (~85%) also reported experiences of violence in education and religious settings.

Nearly all participants who identified as men who have sex with men or trans women reported experiences of violence before age 18 (94%) and violence from a current or former partner (93%). Female sex workers were not asked about violence before age 18 or violence from a partner, as requested by stakeholders from female sex worker networks.

Overall, while all groups experienced violence in numerous contexts, trans women reported experiencing violence in more contexts than female sex workers or men who have sex with men. For example, 80% of trans women reported experiences of violence from police compared to 69% of female sex workers and 66% of men who have sex with men.

Consequences of GBV

Experiences of GBV can lead to devastating consequences. Through the qualitative interviews, all three KP groups reported emotional consequences including depression and suicidality; self-imposed restrictions on movement, behavior or appearance to avoid experiencing violence; lack of access to legal, health and other social services – especially when perpetrators provided these; and loss of income, employment, housing and educational opportunities.

For example, during one participant interview, a female sex worker in Barbados reported:

“It affects me up to this day in a way that I don’t show it but, it does, because it put me into a shell and it lowered my self-esteem and sometimes […] I feel less than a woman… me personally, sometimes I have no hope, there is no escape, it’s like a bond, I mean like a prison you can’t get out of.”

Less than a quarter (< 25%) of participants believed that GBV put them at risk of HIV. Participants who did report a connection between GBV and HIV typically stated the risk came from not using condoms.

Disclosing GBV and seeking services following GBV

Disclosing violence can help victims of violence get the support they need. Many participants reported telling friends and family members about their experiences with GBV. Those who did not disclose expressed that they did not do so due to feelings of guilt or shame and a desire not to relive their experiences.

Only one-third of participants reported ever being asked about GBV by a health care provider and slightly less reported sharing their experiences with providers. However, a majority wished that health care providers would ask them about violence to provide the opportunity for disclosure and referral.

Most participants did not seek services following violence because they thought their experiences were not severe enough to warrant help, thought they would not actually get assistance, or did not know where services were available.

For example, during one participant interview, a man who has sex with men in El Salvador reported:

“They already assume that you’re guilty and that you were the one who initiated everything, the culprit, the criminal. Never the other person. It unconsciously makes you feel like you’re guilty. I was scared. I said, ‘I don’t want to report it, I don’t want to be asked if I’m homosexual.”

Desired services following GBV

Many participants reported that the support they received was not helpful or sufficient, and many wanted access to additional services, especially mental health services and better health care and police services. Participants emphasized that service providers should be respectful, supportive, accepting and protect clients’ privacy.

For example, during one participant interview, a trans woman in Haiti reported:

“I would like it to be taught at the police academy that they should respect people’s rights, that they should know everyone is a person and everyone is free, they have their own choices. They should be taught to respect people’s rights.”

Conclusion

Our study data show female sex workers, men who have sex with men, and trans women experience GBV in public and private settings throughout their lives. Though many KPs disclose experiences of GBV, they rarely seek services from health care providers or police. Many express a desire for services, including being asked about violence by health care providers.

In addition to increasing HIV vulnerability, experiencing GBV impacts KP members’ ability to seek and receive services that could help them prevent, detect and treat HIV. However, as evidenced by participant responses, this link is rarely recognized by those experiencing violence. It is important that HIV programs for KP members make this connection explicitly and provide services that integrate HIV and GBV prevention and response.

Global guidelines like UNDP’s HIV, Health and Development Strategy (UNDP, 2016) and WHO’s HIV Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment and Care for Key Populations (WHO, 2014) already note that the HIV response for KPs must address violence.

It is crucial that we explore how programs and governments can translate study findings into informed policy and practice. Informed by evidence from our study, LINKAGES developed guidelines on how to prevent, detect and respond to violence within HIV outreach and clinical services and conducted gender-transformative trainings aimed at sensitizing police, health care providers, and peers to the needs of KPs and provide them with skills in first-line support tailored to KP members who experience violence.

Additionally, UNDP is working with regional and local civil society organizations to support KPs to document violence and implement a monitoring system, including “zero discrimination” indicators, to provide data on violence and demand attention and policy change from governments.