Written by Alice Olawo, Senior Program Officer, LINKAGES Kenya

Harmful gender norms and inequalities increase violence and HIV risk while limiting the use of HIV services by members of key populations (men who have sex with men [MSM], transgender people, people who inject drugs [PWID], and sex workers [SWs]). Identifying and working to transform the gender norms most harmful to KPs can strengthen HIV-focused programs. LINKAGES conducted a gender analysis in Kenya to examine how gender norms and inequalities affect key populations’ (KPs’) HIV risk and use of services across the HIV prevention, care, and treatment cascade. One of our explicit study goals was to build capacity in conducting a gender analysis among members of KPs. This blog describes our process, outcomes, and the importance of collective capacity building to both the study results and the KPs with whom we partnered.

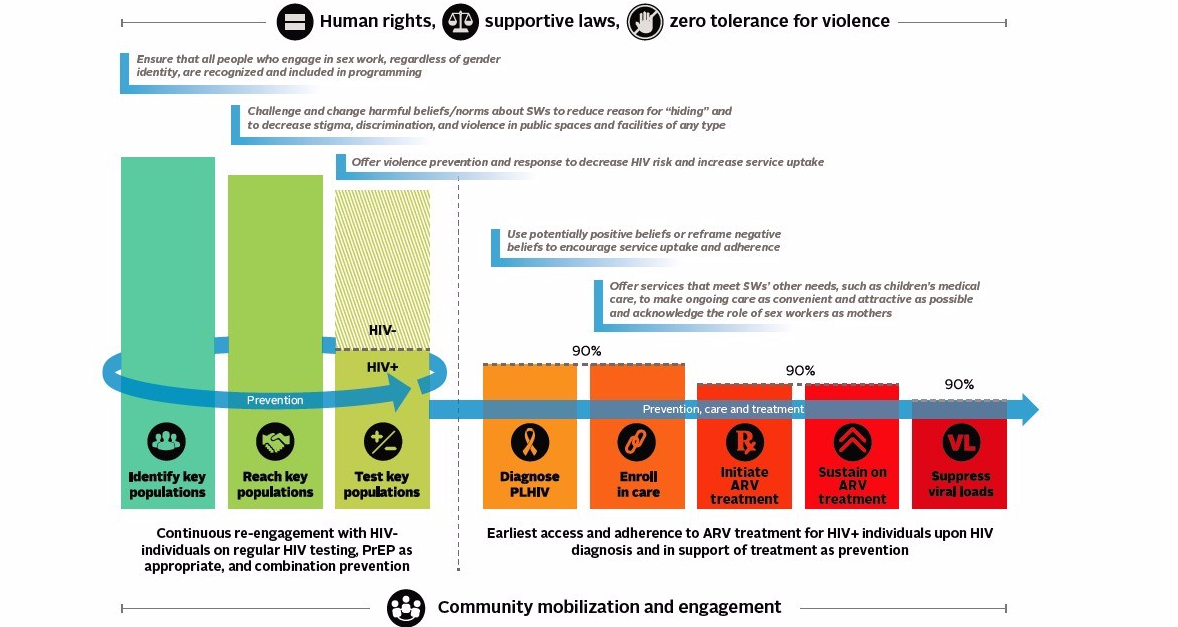

Application of Gender Analysis Recommendations to HIV Prevention, Care, and Treatment Cascade

From the beginning, KP members informed the gender analysis through their participation in a technical working group that participated in study design. The same technical working group recruit and select 10 research assistants (RAs)—representing each of the four KPs. RAs went through a week-long training that covered basic information about all four KPs (which provided opportunities for RAs to teach one another), gender norms and inequalities as barriers to HIV prevention and treatment, and qualitative research. As the study was implemented, RAs worked in KP-specific teams where they received continuous support from one another and from me, the study coordinator, and the principle investigator. By the end of the gender analysis, the RAs had helped design interview guides; recruit gender analysis participants; conduct key informant interviews with representatives from KP-led organizations, government officials, program managers and funders, and health care workers in Nairobi; and package and present the findings from the gender analysis.

Because the study had a specific capacity-building goal, we charted each RA’s progress. I personally observed the gains that each made in qualitative research, including increased confidence in conducting interviews and improved ability to ask probing questions. In interviews and surveys after the gender analysis was completed, RAs reported that their participation in the project enhanced their skills in writing proposals, conducting research, data analysis, and public speaking. I also saw them learn an incredible amount from one another— valuable skills and lessons beyond those learned specifically for the gender analysis. During the gender analysis, SW RAs, who were particularly empowered to stand up for their rights, supported members of other KP groups on effectively advocating for human rights, equality, access to services, and an end to violence. RAs representing SWs, MSM, and PWID also provided important information to the transgender RAs on how to collaborate effectively with the Ministry of Health and their KP programming, a new set of stakeholders for the local transgender-led organization. Since the conclusion of the gender analysis, I have also seen some RAs leverage their new skills, including working as RAs on other studies, leading trainings on research, speaking internationally at conferences, obtaining fellowships, and writing proposals. Read more about the efforts of some of our RAs in the LINKAGES KP heroes blog series.

The capacity-building process, simply by bringing together members of each KP and providing space for mutual teaching and learning, was also able to help build a shared understanding and to strengthen networks. The transgender RA team expressed that they greatly appreciated the opportunity to teach other KP members what it means to be transgender. All the RA teams noted a better understanding of other KPs and a desire to collaborate more closely. And I was impressed by how the RAs across KP groups connected with each other as the study was implemented. They both supported one another professionally—for example, by forming a WhatsApp group to exchange experiences and challenges from their interviews—and personally.

Finally, the benefits of engaging in capacity building by no mean ended with the RAs themselves. As is rightly illustrated in the slogan “nothing about us without us,” it is not possible to conduct research related to KPs without members of KPs leading the way. In our case, the technical working group was an incredible asset but it was the enthusiasm and expertise of the RAs that helped us to go the last mile. The RAs made it possible for the gender analysis to ask the right questions, to successfully seek out a wide variety of key informants, and to hear candid responses from many that would not have been eager to speak to a data collector to whom they could not relate. And the ability to get accurate information from a wide variety of sources meant that the results of the gender analysis could lead to real change. For example, NASCOP has begun to implement a training for health care workers on addressing violence against KPs and is in conversations with transgender-led organizations on expanding KP programming to include transgender individuals. And all of these efforts will continue to be supported by the same RAs who were so instrumental in collecting the original findings.

If you are interested in conducting a gender analysis with KPs that includes a capacity-building element, check out our new KP Gender Analysis Toolkit. If you would like to read more on the results of the gender analysis, check out the four-part Nexus of Gender and HIV brief series. The briefs can be used by individuals and organizations that deliver services to members of key populations; those participating in program design and monitoring and evaluation; and decision makers and funders supporting the programs.

Bio

Alice Olawo works for the LINKAGES Kenya Project as a senior program officer. Prior to this, she worked as the study coordinator during the implementation of the LINKAGES Gender Analysis Study in Nairobi, where she learned the importance of involving KPs in the process of conducting research and the benefits of building their capacity in this way.