Written by Kim Dixon, Gender-Based Violence Consultant, LINKAGES

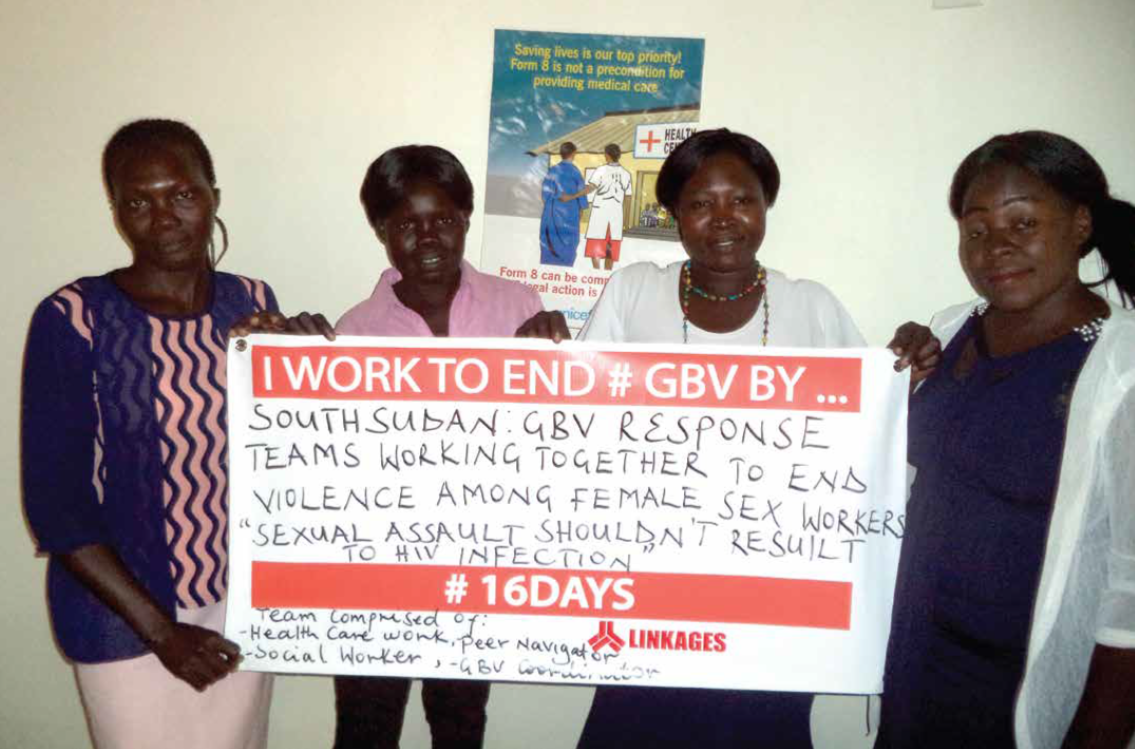

LINKAGES’ South Sudan team shares their commitment to addressing GBV during the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign.

Before joining the LINKAGES project, I spent most of my career developing, managing, and evaluating gender-based violence (GBV) prevention and response programs for women and girls in emergency, post-conflict, and development settings, as well as in the U.S. In my role as a GBV consultant for LINKAGES, I support country programs to develop and implement violence prevention and response (VPR) programs for key populations (KPs). I have learned directly from KPs themselves about the multiple layers of stigma, discrimination, and violence that prevent them from seeking and accessing services after they experience violence.

Because KPs’ behaviors are frequently viewed as not conforming to traditional gender norms and are often criminalized (e.g., sex work, homosexuality, drug use), they are afraid to seek help after experiencing violence due to fear of being arrested, shamed, or denied services. For these reasons, unless we become proactive in identifying KP individuals who experience violence, we are missing opportunities to link victims to important post-violence services, such as HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and emergency contraception. The chance to address any barriers that interfere with adherence to ARVs among people living with HIV – such as not taking ARVs for fear of an abusive partner finding out their HIV status – is also missed. The failure to address violence among KPs ultimately limits our ability to achieve the 90-90-90 goals.

Health care workers in South Sudan practice screening for violence during role plays.

This is why much of the VPR work in the context of LINKAGES focuses on building the capacity of project staff — including health care workers and outreach workers — to be proactive in identifying violence among KP individuals via violence screening. If we wait for KPs to disclose violence, we may not hear about it due to the barriers just mentioned. Instead, training providers to ask KP members about violence and building their skills to provide first-line support increases the likelihood that KP victims will get linked to important, time-sensitive post-violence clinical services and may increase uptake of and adherence to HIV care and treatment.

Success in South Sudan

Some LINKAGES countries that are implementing violence screening and response interventions are already showing good results. In South Sudan, health care workers were trained on core concepts related to sex and gender, harmful gender norms, and the connection between violence and HIV. They then developed skills for screening KP individuals for violence and providing first-line support to KP victims, including linking them to health, psychosocial, and legal services. Since the training, Jennifer Iden, GBV coordinator for LINKAGES South Sudan, and the rest of the team have successfully integrated VPR screening and response services into existing HIV prevention, care and treatment services. During the last quarter (July-September 2017), 608 female sex workers were screened for violence by health care workers during mobile clinics. Of those screened, 293 (48 percent) reported experiencing sexual violence in the past three months. In turn, 87 (30 percent) of those reporting sexual violence were eligible for PEP, which means that health care workers identified the sexual violence within 72 hours of the assault. Of the 87 women who were eligible for PEP, 87 (100%) received it and were able to reduce their risk of HIV infection.

Health care workers are trained to screen KPs for violence.

The LINKAGES project in South Sudan is a success story that illustrates the direct link between violence screening and increasing KP victims’ access to critical HIV prevention services. I hope South Sudan’s success inspires others to integrate VPR activities into their HIV programming for key populations.