Written by Karah Pedersen, Senior Technical Manager, IntraHealth International

It is easy to forget that doctors, nurses, and other health care workers are just like everyone else. They even have feelings.

At a recent Health4All training, a social worker in Suriname explained, “Health workers say that they don’t want to put aside their upbringing or values, and they don’t want to say, ‘Ma’am’ when you are a biological man. They say, ‘If you have a name like Trixie, I will call you Trixie, but I will not call you Ma’am. What about my feelings?’”

Health workers’ feelings — as well as a constellation of other factors, including cultural norms, beliefs, and structural inequities — guide how they behave toward and deliver services to key populations. Unfortunately, many members of key populations report unwelcoming, disrespectful, or discriminatory treatment by health workers that directly affects whether they will seek or continue HIV services.

After so much incredible progress toward controlling the HIV epidemic, the powerful ripple effect of stigma and discrimination across the HIV cascade remains a major barrier to epidemic control.

That is why LINKAGES is learning how to talk with health workers about their feelings in productive ways — and truly tackle how to support health workers to provide key populations with HIV-related services that are free of stigma and discrimination.

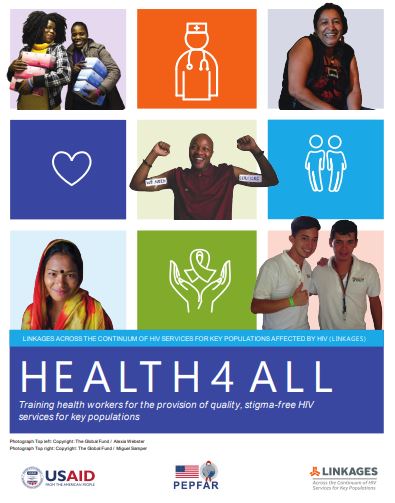

LINKAGES’ project partner IntraHealth International has led the development and adaption of the Health4All campaign to better assess, address, and strengthen the capacity of health workers to work with key populations. As part of the campaign, IntraHealth developed a training strategy that involves local adaptation and use of the training guide Health4All: Training Health Workers for the Provision of Quality, Stigma-Free HIV Services for Key Populations (available in English and French). The aims of Health4All are to guide self-reflection among health care workers and to improve their empathic, clinical, and interpersonal skills to enable them to provide high-quality, comprehensive services for key populations that are free of stigma and discrimination. You can learn more in this previous blog post about the training guide and how it was developed. Complementing the Health4All training strategy, LINKAGES regularly monitors the quality of services among its partners and helps them to make changes, as needed, to improve service delivery.

Since 2016, IntraHealth has worked with 14 LINKAGES country offices to deliver the Health4All trainings to more than 800 participants. It has been an invaluable learning process, and we at IntraHealth and LINKAGES have continued to revise and adapt the training guide and complementary strategies to reflect insights from the trainings. Particularly striking has been the personal transformation of health workers after they have completed the training. At the beginning of the trainings, many health workers have little to no knowledge or awareness about gender, sexuality, and how to address the unique needs of key populations to curb the HIV epidemic.

“With greater detail, I came to understand the concept of key populations, the factors that make them vulnerable, the challenges faced by key populations, and the constraints of professionals in dealing with [these issues].” – Participant from Health4All Training of Trainers in Angola

Central to the training approach is meaningful involvement of local constituencies of sex workers, men who have sex with men, transgender people, and/or people who inject drugs by including them as co-facilitators, participants, and panel members. The power of conversation between health workers and members of key population groups is clearly transformational for many health workers.

Surprisingly, it has been relatively easy to create training environments that are safe spaces for open and honest dialogue between health workers and key populations. Most participants — both health care workers and key population members — are respectful of one another. Health workers are eager to learn more about key populations, especially their personal experiences trying to access HIV or other health care services. To illustrate the impact that stigma and discrimination can have on anyone, the training also encourages health workers to share their own experiences of feeling stigmatized or discriminated against; everyone always has a story to share.

Health workers, like the rest of us, want to talk about their feelings. But more than that, they want to serve their clients as best they can.