Brian Pedersen, Technical Advisor, Social & Behavior Change, FHI 360

Manya Dotson, Senior Technical Advisor, Marketing & Demand Generation, Jhpiego

Endalkachew Melese, Senior Technical Director, Project HOPE Namibia

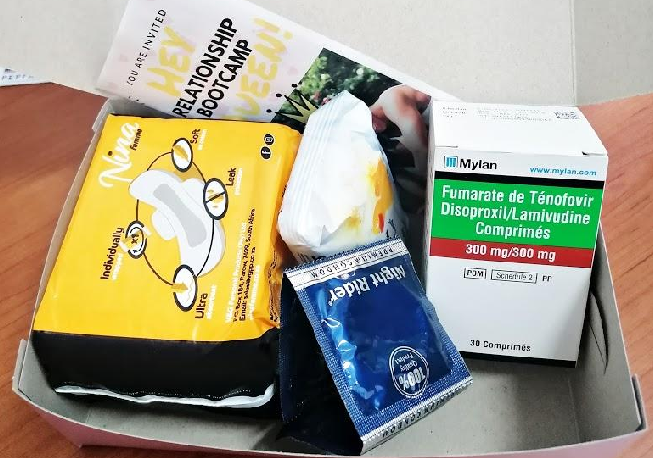

Starting in November 2020, the CHOICE project worked with Project HOPE Namibia (PHN) to review and address gaps in its oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) demand creation activities. PHN manages PEPFAR/USAID-funded DREAMS programs in three regions of Namibia, reaching tens of thousands of adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) with HIV interventions. When PHN and its partners added oral PrEP to their program in late 2018, they adapted demand creation tools and materials from other countries. By 2020, lower than expected PrEP uptake exposed the need for a more comprehensive demand creation approach.

Early on, we decided to use a design sprint since PHN needed to move quickly to boost demand and reach annual targets for PrEP uptake. Adapted from the model developed by Google Ventures, a design sprint applies a step-by-step, collaborative methodology to guide participants to quickly diagnose gaps, develop solution prototypes, and test those prototypes with clients.

While a design sprint ideally takes place in-person, due to COVID-19 we adapted the model for virtual delivery with facilitators and participants based in different time zones. Leaning on the remote adaptation suggestions developed by the model’s originators, we ended up spreading content across seven two- to three-hour online sessions interspersed with asynchronous “homework” assignments.

In this post, we describe some of our key lessons learned in facilitating a virtual design sprint.

What worked well

- The virtual format allows broader participation from project staff since there are no travel costs limiting who can participate. Our virtual sprint engaged nine project staff from across several regions, which added to the richness of discussions and outputs by leveraging more diverse viewpoints and experiences.

- Homework provided participants with more unstructured time and freedom that often led to unexpected and creative outcomes. Participants were given space to explore lines of inquiry outside the confines of a windowless conference room. One participant visited a local beverage distribution company to understand how they try to influence public attitudes affecting the sale of carbonated drinks.

- Even though it was limited, the testing of solution prototypes is still one of the best ways to client needs. For example, when testing a male partner engagement script, the team discovered that men want to be treated as individuals with their own unique needs, not just the sexual partners of AGYW. As a result, male partner engagement tools were modified to include messages encouraging men to not only support their partner’s PrEP use but to also seek out PrEP services for themselves.

What we learned

- A virtual design sprint is not a shortcut – it often requires more time to prepare and the same commitment from participants as an in-person sprint. Treating a virtual sprint as something that is done in addition to regular work is a recipe for a less productive sprint. Both facilitators and participants need to dedicate time to fully engage in a virtual sprint.

- It is difficult to prototype and test solutions when facilitators and participants are spread across several geographies. Without being in the same physical space, it was difficult for us to provide support and guidance during prototype development and testing. And when prototypes were presented, it was difficult for other participants to make connections between ideas.

- It is challenging to build and maintain momentum in a virtual sprint. A design sprint is purposefully compact and fast-moving so momentum can force quick decision-making and creative thinking. The virtual nature of our sprint required shorter sessions (which made it difficult to build momentum) spread over a longer period (which made it difficult to maintain momentum).

How we hope to do better

Building on our Namibia experience, we’ve already tinkered with our virtual design sprint model, hoping to mitigate the challenges highlighted above.

- The biggest change has been the adoption of a hybrid model where in-person activities complement virtual sessions. Virtual sessions are used to “tee up” and review the results of design activities, which are completed by small teams working in-person. This hybrid model should solve our momentum problem since it allows for a more condensed schedule and includes (masked)face-to-(masked)face interactions.

- We’re also starting to limit participation to people working in the same geographic area. While this sacrifices the benefit of broader engagement, we felt the benefit of in-person collaboration, especially during the solution prototyping and testing phases, required it.

Our experience shows that virtual design sprints can work – over the course of seven sessions and several “homework” assignments, the team produced client-tested tools and materials that are being finalized and prepared for rollout. But the virtual design sprint format is tough. Tough for participants who have to stare at a screen for hours and tough for facilitators who need to be even more diligent in their preparations. While in-person design sprints will remain our strong preference, if we need to go virtual, there are some small things that can be done to make them more productive.