Written by Rafaela Egg, LINKAGES Angola; Ben Eveslage, FHI 360; Denizia Pinto, LINKAGES Angola; & Caitlin Loehr, IntraHealth International

“Here they come again with another ‘big idea,’ another innovation, to see how we can improve.” – Dario, community peer educator, Luanda, Angola

Dario was not hopeful about using online or mobile platforms for his HIV outreach work in Angola. At first glance, online HIV service delivery was a “white elephant” in Angola — totally unrealistic given the local context (such as the high mobile data costs, low internet penetration, and competing priorities of communities affected by HIV). On the other hand, with the ambitious goal to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 and ever-increasing mobile and social media use globally, this white elephant was also the “elephant in the room.” It was so obvious that HIV programs needed an upgrade for youth and the digital generation who connect and make consumer and health decisions through media they access online. Through much trial and error, Dario and a few other community members helped translate global technological approaches to their local reality, simplifying the work of peer educators and reaching more at-risk clients online.

Dario worked as a community HIV outreach worker in Luanda, Angola. He was hired by the USAID- and PEPFAR-supported LINKAGES project. LINKAGES is the first and currently largest global HIV project from the U.S. government focused on key populations, with programming in more than 30 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. In Angola, the project supports community, public-, and private-sector partners to improve HIV services for key populations — those at highest risk for HIV — including gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and transgender people.

Community members on the front lines of the HIV response in Angola (like Dario) were no strangers to change. They adapted their approaches to meet the dynamics of the HIV epidemic, but they were hesitant to embrace the LINKAGES project’s vision of going online to accelerate the impact of HIV programs. There is merit to this resistance because of the cost and availability of mobile data and devices to use such data. For instance, compared to 51% internet penetration and 38% social media use in Southern Africa, only 19% of Angolans are connected online and 11% are social media users. High cost of living and the rapid devaluation of the local currency also undermine the affordability of mobile data and smartphones.

Despite this challenging scenario, it was common to hear from program beneficiaries in Angola that gay men and other MSM are increasingly meeting sexual partners and friends online through Facebook and WhatsApp. Many said they used Facebook Zero, a version of Facebook without images, GIFs, and videos that does not carry mobile data charges on Angola’s Unitel mobile network. The project staff then went online to find out more. A mapping exercise conducted in March 2018 identified 64 Facebook groups where gay men and other MSM could be reached with a combined total membership of roughly 280,000 profiles.

Evidence of the potentially large number of people on social media, however, did not convince the outreach team. “Talking about health is not a priority for gay men when they are online. It is even worse if the topic is HIV!” said a disheartened Garcia, another online peer educator. The idea was that gay men go online to look for sex, so the peer educators strategized that if they presented themselves online as any other gay man looking for sex under an anonymous Facebook profile, it might attract men for a chat where eventually the topic of HIV or sexual health could be introduced. Most found this a daunting approach; they received many provocative photos and experienced very little success. In two months, the peer educators were not able to bring a single client in for health services from those they engaged with online.

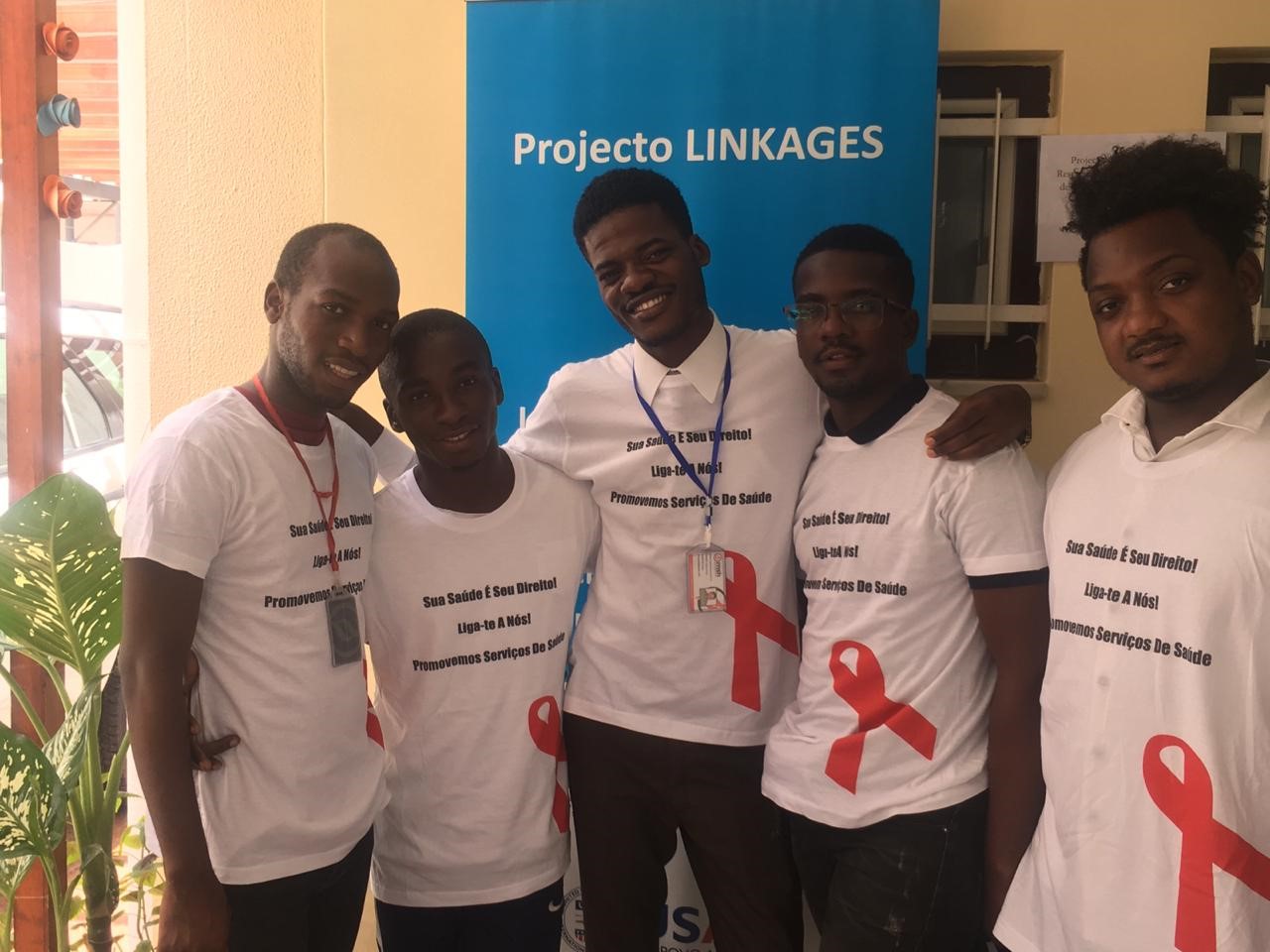

The team decided to change their approach. They trained five peer educators to use a social network outreach strategy online. Global training materials were carefully tailored for the Angola context to enhance peer educators’ understanding of their role in an online environment, provide them with skills to improve their online presence (i.e., the quality of their posts, images, and content), strengthen their ability to identify clients’ sexual health needs, and support clients’ access to offline services through referrals and follow-up.

The idea behind the social network outreach approach was for peer educators to move past drawn-out conversations with clients seeking sex or companionship online by presenting themselves as the trained peer educators they were. The peer educators developed their own professional profiles, despite their initial hesitancy about openly presenting themselves on Facebook. Henrique, another peer educator hired by LINKAGES, recalls, “It was not easy. I was very insecure.” For the community of gay men and other MSM in Angola who have largely been hidden or behind the veil of anonymous social media or dating profiles, it was a bold and important decision to go online with their real identities in the name of HIV outreach. Peer educators created their profiles in a way they felt maintained their own safety and confidentiality while also helping them achieve their outreach goals. This approach helped them to build and maintain trust with fellow MSM online, and after the shift, online chats between clients and peer educators started to flow.

The outreach staff quickly recognized the broader value of their approach. One peer educator, Kudibanza, said, “We are discovering the potential of online and mobile platforms to reach our peers as we mature our online communication skills. Having a professional profile enhances our role as peer educators. Our peers are seeing us as a reference for the services, and they are coming to us spontaneously.”

Challenges still occur. Staff are asked for sex, and they sometimes face threats and other forms of harassment. The difference now is that they are better equipped to deal with these instances so that they keep the bond with the client but also stay safe. As one peer educator, Michel, put it: “We can better manage sexual harassment. We are able to respond to it in a professional fashion and still redirect the conversation to the topic of health, whereas before we would just end the conversation abruptly.” Daily supervision helped ensure that online peer educators adhered to safe and effective online outreach strategies and that new challenges and client issues could be addressed quickly.

Eventually, the online outreach efforts led to people arriving at clinics. The program reported that 87 clients who were originally reached online went to clinics between April and August 2019. Among them, 74 tested for HIV and 16% were diagnosed with HIV. Compared to a 1% case-finding rate for HIV testing among gay men reached through physical outreach, the early data suggest that online outreach is considerably more targeted and efficient. Moreover, the individuals diagnosed as a result of the online outreach work accounted for 36% of all HIV-positive cases detected among gay men by LINKAGES from April to August 2019.

By carefully adapting the approach to the local context, the online outreach team found that they were meeting an unmet need by reaching previously unreached populations at high risk of HIV and helping them link to HIV testing and treatment. The LINKAGES project in Angola closed at the end of September 2019 and the team of online outreach workers on this project will disband. However, peer educators of another local LGBTIQ NGO have been trained on the same approaches to support HIV services to online gay men and other MSM in Angola.