Michael Cassell, Senior Technical Advisor, EpiC

Bettina Kaye Castañeda, Senior Strategic Information Advisor, EpiC Philippines

Joven Santiago, Social & Behavior Change Communications Technical Advisor, EpiC Philippines

With an estimated 16,000 new HIV infections per year—sustained primarily by gaps in HIV service access for men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women—the Philippines is one of the few Asian-Pacific nations experiencing an expanding HIV epidemic. Now, COVID-19 is complicating the nation’s ambitious efforts to curb rising HIV infections. The Philippines has had more than 2.2 million reported cases of COVID-19 and more than 35,000 deaths, which have stretched the capacity of the health system. The national HIV program reported year-over-year declines in HIV treatment initiation and access to viral load testing, as well as increases in HIV treatment interruption, in its 2020 report on the impact of COVID-19 on the HIV epidemic in the Philippines.

Nevertheless, the dedication and ingenuity of health care providers in the Philippines prevented the situation from becoming much worse. Faced with the paradox of sustaining access to health services while supporting physical distancing to prevent COVID-19 exposure, the Philippines joined many other countries in turning to online solutions to maintain connections for patients. Treatment facilities offered teleconsultations and mobile-messaging-based ordering of HIV treatment prescription refills via courier delivery. To facilitate initiation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) while minimizing risks of COVID-19 exposure at clinical facilities, systems were established to collect samples for initial laboratory assessments in the community, deliver these to laboratory sites, and transfer the results via secure email to clients and PrEP providers. In the process, the Philippines aimed to take remote services a step further—going online to improve support for the health care providers on the front lines of the response to HIV and COVID-19.

With funding from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Meeting Targets and Maintaining Epidemic Control (EpiC) project has been working with local authorities and civil society partners in Greater Manila to establish online and virtual platforms to support and safeguard HIV service providers. These efforts have included giving online interactive training to enhance provider skills to support clients through face-to-face and online communication, and to commence implementation of PrEP in the Philippines, a critical priority to stop new HIV infections.

During August 2021 alone, as Manila faced widespread COVID-19 lockdowns, the EpiC Philippines team supported five virtual trainings for health care providers on topics including client-centered case management and support; data management, security, and analysis; and screening for and responding to intimate partner violence. The smallest of these trainings included a dozen participants and the largest more than 65.

In addition, EpiC has established routine monthly virtual sessions with clinical teams at supported sites to review HIV program implementation challenges and opportunities, and to check in on the well-being and needs of team members. During these sessions, teams review progress toward service delivery goals, brainstorm solutions to challenges, and identify and advocate for needed caregiver support and resources. These meetings play a key role in supporting the esprit de corps and morale of the clinical teams amid the unprecedented pressures of combating both HIV and COVID-19.

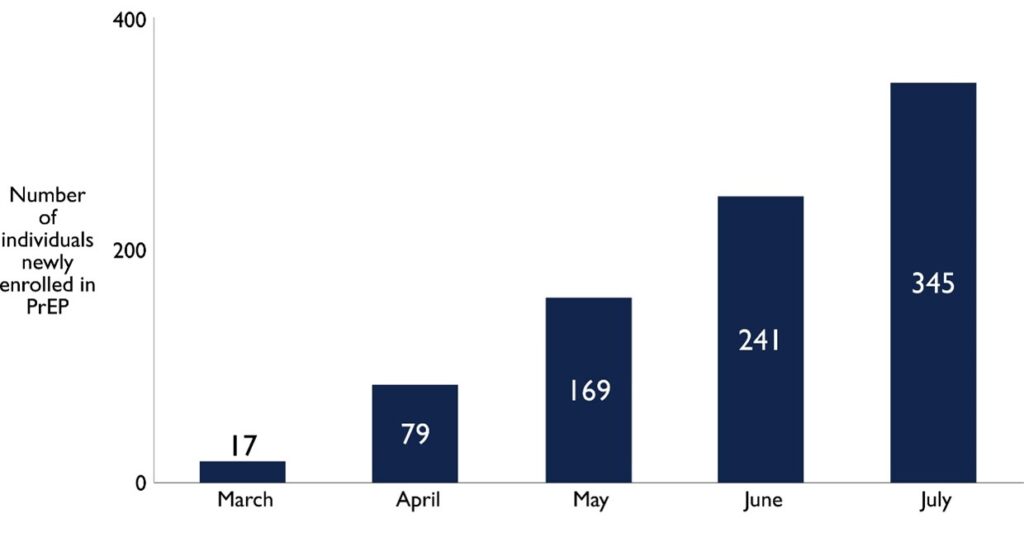

It is early in the implementation of these virtual provider support activities, but evidence is emerging of the potential benefits of sustaining and expanding access to high-quality HIV services despite persistent COVID-19 related challenges. For example, through virtual data reviews in March and April, EpiC and its partners identified early warning signs of slow PrEP scale-up. Although the root causes seemed largely associated with supply constraints, EpiC and partner staff were able to facilitate re-allocation of unused supplies and fast-track delivery of new supplies starting in June. Associated improvements in new monthly PrEP enrollment are depicted in Figure 2.

Looking ahead, the project plans to help the Philippines implement an expanding array of differentiated HIV services and solutions to respond to client preferences and to support safer and more convenient access during COVID-19 and beyond. Among these services are self-led options like HIV self-testing, expanded online service navigation, and additional virtual support including confidential online counseling and case management. EpiC’s provision of online training and support to providers will help to accelerate the scale-up of these and other critical services by safely building provider skills while mitigating COVID-19 exposure risks.