Aubrey Weber, Technical Officer, Research Utilization, FHI 360

Benjamin Eveslage, Technical Advisor, Online HIV Services, FHI 360

This blog post was originally published here on ICT Works.

We are told to #stayhome, avoid gathering in groups, keep at least two meters from others, and frequently and thoroughly wash our hands – all to do our part to help flatten the curve. These responses to COVID-19, while essential, now present unique challenges for other global health programs.

The global response to HIV, in particular, is greatly affected by new physical distancing measures, lockdowns, and quarantines. HIV programs can and should use online and virtual platforms to support community mobilization and engagement as well as to help clients to continue accessing HIV services, remotely and through home delivery or more convenient commodity distribution points.

As of this year, more than 67 percent of people globally are mobile phone users and nearly 60 percent are connected online; this includes people living with HIV and key populations at risk of HIV. In the context of COVID-19, virtual and online channels can help HIV programs continue service delivery to those who need it most. And, regardless of the presence of a pandemic, it is time for HIV programs to shift toward connecting with more of their target audience online.

The following COVID-19 digital responses can be used to mitigate the impact of coronavirus on HIV services.

1. Using Social Networks for Outreach

Social network outreach helps HIV programs reach and engage populations at risk for HIV through one-on-one chats, either through online or virtual platforms. This approach can be:

- Implemented by training existing or new outreach staff to contact their peers and other members of their networks online

- Extended to untrained community members, to whom HIV programs can award incentives for mobilizing their friends online to get tested

Consider providing some messaging guidance to outreach staff or volunteers to guide their conversations with clients, especially related to clients’ health and HIV needs during the pandemic.

2. Virtual Case Managers

Virtual case management is an approach that can help peer navigators and case managers to provide remote support to clients living with HIV. The main objective of this approach is to encourage continued access to antiretroviral therapy (ART), but it can also be applied similarly for PrEP use among people who are at high risk for HIV and to address other counseling needs.

Virtual case managers require training on how to provide online or phone-based client support and should be provided a mobile phone with airtime and client register (or client management software) where they can track their clients, find their contact information, and record key variables about the clients´ status and service needs.

Virtual case managers serve a crucial role in coordinating with clients, other virtual service providers (like mental health counselors), and physical service sites to ensure that clients receive the best advice and support to access ART and to prevent loss to follow-up and interruption in treatment.

3. Online Reservation App (ORA)

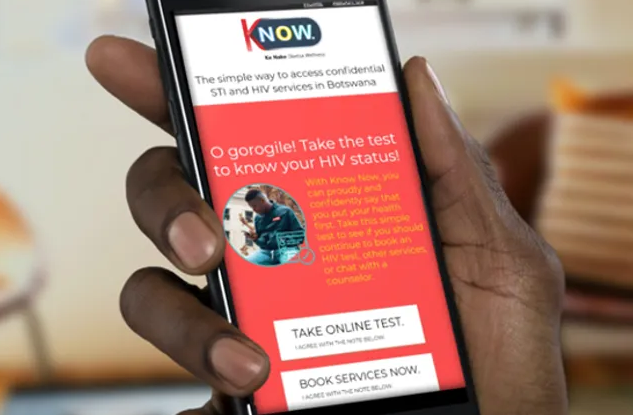

ORA is a web application developed by FHI 360 to help HIV programs manage online outreach, service referrals, clinic reporting, and client case management. On ORA´s front end, clients can assess their own sexual health risk, receive tailored service recommendations, and book appointments across partner clinics.

Outreach and clinic staff can also book appointments on clients´ behalf if the client does not have mobile data or a smartphone. This is an entirely online process, from outreach to arrival at clinics. The absence of paper forms and referral slips is especially important in the context of COVID-19.

Clinics can view upcoming appointments, call clients to screen for COVID-19 infection, and use the ORA interface to report services provided to clients during their appointment. Case managers can be assigned appointments on the ORA back end to view clients’ status and provide follow-up services. ORA is uniquely branded for each HIV program and is now used in Thailand, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Kenya, Botswana, Eswatini, and Mali.

4. WhatsApp for Remote Support

With more than two billion users in over 180 countries, WhatsApp is an ideal means of staying in touch with others. The app, which first started as an alternative to SMS, is free and offers simple, secure, and reliable messaging and calling. HIV program implementers can use WhatsApp for virtual collaboration and to provide technical assistance to remote-based partners, staff, and clinicians.

In Jakarta, Indonesia, the lockdown limited the ability of LINKAGES staff to continue hosting physical meetings and trainings with health providers. They switched to using WhatsApp for weekly discussions. With more than 200 participants, these sessions have helped roll out facility-level responses to COVID-19, including multimonth dispensing of ART, which allows people living with HIV to visit health facilities less frequently.

To learn more about the approaches mentioned in this post, visit LINKAGES’ Going Online resource page and see other considerations for mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on key-population-focused HIV programs.