Maggie McCarten-Gibbs, Senior Technical Officer, FHI 360

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a global mental health crisis, making the provision of mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) a critical component of comprehensive HIV programming. In the first year of the pandemic alone, the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by 25 percent. Given the proximity to the initial outbreak, Southeast Asia was one of the first regions affected by the pandemic. One study in the region found that 18-months after the initial COVID-19 outbreak, 46 percent of people in the study experienced severe or extremely severe symptoms of depression, 49 percent experienced symptoms of anxiety, and 36 percent experienced symptoms of severe stress.

This increase in the incidence of mental health conditions has direct impacts on HIV programming. Not only do mental health conditions and other intersecting vulnerabilities increase the risk of HIV infection, but people living with HIV (PLHIV) have an increased burden of mental health conditions. Mental health conditions are associated with lower retention in HIV care, increased risk behaviors, and lower engagement with HIV prevention services. Health care staff are also experiencing high levels of anxiety, depression, and burnout. Burnout was common prior to COVID-19 and has been exacerbated by the pandemic.

In February 2023, the Meeting Targets and Maintaining Epidemic Control (EpiC) project, led by FHI 360 and funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), convened a three-day meeting in Thailand with technical and programmatic leaders in HIV programs for key populations from Thailand, Cambodia, Myanmar, Nepal, and Vietnam. This exchange offered teams an opportunity to share lessons learned, discuss common challenges, and inform FHI 360’s global framework for implementing MHPSS programming.

Five key takeaways emerged from the meeting:

1. Effective screening for mental health conditions is complex and requires adaptations for country contexts. There are many evidence-based, validated screening tools, but approaches to screening vary by country, and even region-to-region. For example, one implementing partner site in Vietnam has clients self-administer the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), while other tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-C (AUDIT-C) are administered by a psychologist or health care worker. Other sites follow the conventional approach of having health staff administer all tools. This varied approach to screening can cause confusion when selecting tools.

During the meeting, Asia Regional EpiC teams shared challenges they have faced when deciding how to screen. For example, it is not always clear which tools should be selected, how they should be administered and by whom, or if screening is appropriate in each setting. Some teams also reported that it can be difficult to find screening tools that are culturally appropriate. In Vietnam, some clients find standard screening questions too invasive. To address this the team tries to weave the general themes from screening questionnaires into conversations with clients. In Nepal, teams have struggled to find a validated tool available in all the relevant languages. They have also found that when screened at clinical facilities, many more people score as at risk of depression or anxiety, than when screened in the community during outreach.

In both Vietnam and Nepal, the percentage of clients presenting as at risk for anxiety or depression has been lower than expected. For example, in Vietnam about 1 percent of the people screened had results indicating they were at risk for depression or anxiety, but a recent meta-analysis estimated that the prevalence of depression in Vietnam was 14 percent. Due to these differences, EpiC teams in these countries are asking important questions about continued training for those administering screening, the role of mental health stigma, where people are most likely to feel comfortable truthfully answering screening questions, and how to introduce the concept of mental health in a normalizing way. Each team remains committed to further honing their processes and fostering learning between sites to maximize the ability to effectively identify those who need care and improve both client and provider satisfaction with the experience.

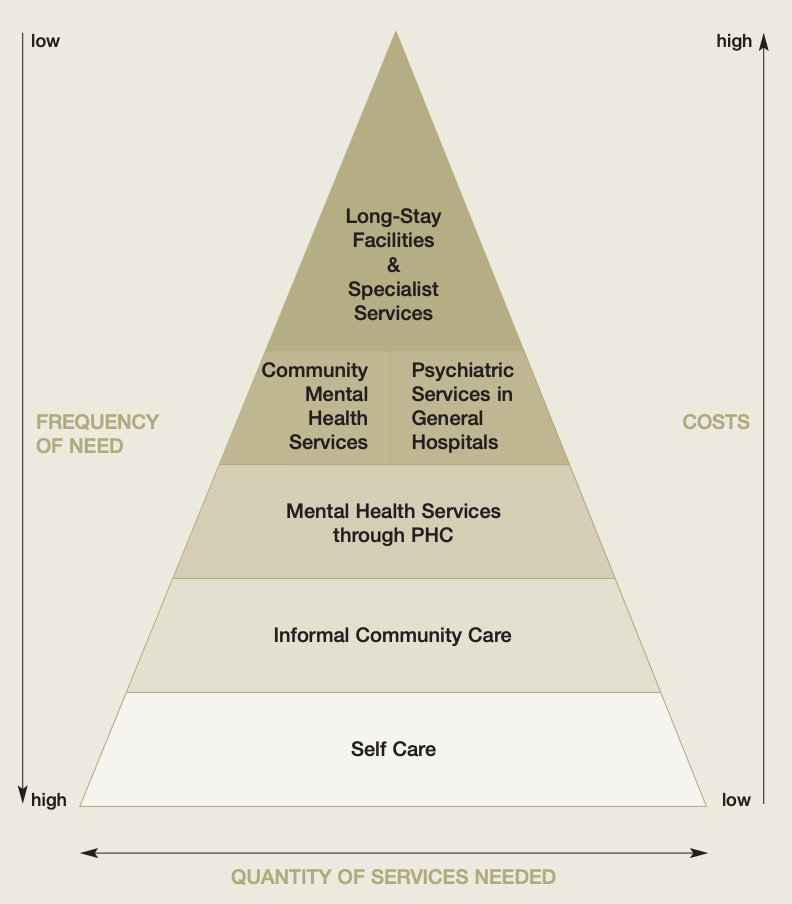

2. A mix of interventions is needed in all settings. Not only are there many screening tools, but there are also many effective interventions to address mental health conditions. While longer and multi-level interventions generally have greater and longer-lasting benefits for individuals with complex mental disorders, they are costly and less feasible to implement, especially in settings with limited psychologists or other specialized clinicians. As shown in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) pyramid framework for the optimal mix of MHPSS services (Figure 1), a mix of MHPSS services is needed to address different levels of MHPSS need. Most people can have their needs addressed by self-care management and informal and primary care staff provided community-based mental health services.

Figure 1. World Health Organization (WHO) pyramid framework for the optimal mix of different mental health services. From: Organization of services for mental health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003 (Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package).

In Myanmar, EpiC collaborates with the USAID HIV/TB Agency, Information and Services (AIS) Activity, being implemented by Community Partners International. AIS supports Population Services International, Medical Action Myanmar, Lan Pya Kyel, and other organizations to integrate MHPSS programming into HIV services. AIS primarily provides services on the lower levels of the WHO pyramid. These services can be provided to groups or individuals and are designed to be easy to access. They are available to anyone without targeting specific mental disorders and do not require asking about mental health symptoms. Specific MHPSS activities vary in Myanmar, and their objectives do as well. They range from reducing distress, improving social engagement, improving overall well-being, and increasing daily functioning. AIS uses several evidence-based approaches to address the needs of clients with less severe mental distress. In psychological first aid (PFA), providers with limited training give empathetic, supportive, and practical help to people experiencing a crisis. Basic psychosocial skills (BPS) and BPS+, which can also be administered by those with limited training, aim to build a foundation of psychosocial skills among all essential workers. The Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA) Short Sessions is a multi-problem intervention which combines treatments for a range of mental health issues into a single intervention.

While effective for most people, these interventions are limited in terms of the support they can provide to people who have moderate or severe distress, or other mental health problems. Therefore, providing formal community-based and hospital-based psychiatric services, as well as specialty mental health services, allows for broad support to address common mental and behavioral health problems. For those with higher levels of distress, AIS uses interventions such as Problem Management plus (PM+)—a World Health Organization psychological intervention delivered by trained non-specialist lay-providers in five sessions to adults impaired by distress—and CETA. CETA full sessions are meant to address symptoms of common mental health problems, such as trauma-related symptoms, depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, substance use problems, and safety issues such as suicide and/or interpersonal violence.

The level of intervention intensity varies depending on the severity of the condition and symptoms, the level of client need, and the cultural context. A specific intervention will not be appropriate in all settings, and not all clients will benefit from all interventions. While one size does not fit all, a mix of MHPSS interventions meeting each level of the pyramid is needed to meet the range of needs that exist.

3. Mental health screening and services need to be adapted for key populations (KPs). There are very limited options for MHPSS services tailored to the needs of transgender populations, but data from Thailand show a substantial need for services, including for depression. Of the 291 transgender women screened at the Tangerine Clinic, 55% presented with depressive symptoms. Because transgender women often have negative experiences in traditional health care settings due to stigma and discrimination, screening and treatment for this population should be available outside of that setting. In response to this need, the Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI) developed a peer-led depression screening tool that was embedded into routine HIV and sexual health service provision at IHRI’s Tangerine Clinic. Transgender counsellors and nurses were trained by a psychiatrist to implement the screening and to conduct psychosocial support. They could then refer as needed, within or outside of Tangerine Clinic. The high acceptance rates of referrals within the Tangerine Clinic (no referrals were accepted outside of the Tangerine Clinic) demonstrated that integration of transgender-friendly MHPSS services is feasible using KP-led strategies that include the full range of services on-site. Building off this success, IHRI scaled up the mental health screening services to other community-based organizations under EpiC Thailand, including Mplus Foundation in Chiang Mai, Rainbow Sky Association of Thailand in Bangkok, and Service Workers in Group Foundation in Bangkok and Pattaya.

4. Providing care for caregivers is essential. Caregivers, those implementing services at any level, are the backbone of all health projects. This includes everyone involved in the program, not just physicians and nurses. In order to implement MHPSS programming for program beneficiaries, implementers must ensure there are adequate resources, training, and staffing to effectively add MHPSS components to existing HIV programs, including for the staff. The EpiC team in Vietnam serves as a prime example of how this support can be institutionalized effectively. The team prioritized the well-being of their staff prior to implementing mental health programming more broadly. The team was experiencing increased burnout from surge implementation during COVID-19, alongside the personal stress of lockdowns and isolation. Over a nine-month period, EpiC Vietnam staff transformed the dynamics within their team to prioritize self-care, mental health, and team building. This included incorporating mindful moments into HIV leadership meetings and identifying local mental health providers accessible to staff. As a result, staff have become more innovative. Following this investment in team members, MHPSS programming has been strengthened. To date more than 20,000 program participants have been screened and those identified as being at-risk have been referred for care. The program also recognized the needs of caregivers, focusing on building the skills of healthcare workers to prioritize self-care and self-compassion as a coping tool. In less than two months, EpiC provided more than 30 counseling sessions, six hours of training, and 12 skill-building workshops for health care workers themselves.

5. More needs to be done to monitor and evaluate MHPSS programming. Both the inputs and outcomes of MHPSS investments can be hard to quantify. For example, documenting the number of therapy sessions does not predict whether a mental health condition was resolved in the same way that counting doses of an antibiotic might. Even “success” can be hard to define. Is it increased access to MHPSS, fidelity to a specific intervention, increased demand for mental health care, changes in clinical outcomes among those served, practitioner skill and capacity, client satisfaction with the larger HIV program, and/or changes in HIV-related outcomes? In addition, programs must think through how they measure inputs (group versus individual therapy, services delivered by a lay provider versus a mental health clinician) and unintended consequences, including those related to mental health stigma.

Strong communities of practice will be important for implementers introducing new programmatic approaches. As HIV programs seek to integrate MHPSS into their existing services, they will face barriers—stigma against mental health conditions, the lack of resources invested in mental health care, the belief that physical health conditions should take priority, the cultural and clinical complexity in accurate diagnosis, and the dearth of clinical experts. Having a community with which to meet these challenges and to identify both questions and answers is vital. There are still many questions left to be answered, and EpiC country programs are continuing to learn from one another. Program teams are working closely together, along with technical experts, to build robust MHPSS programming within existing HIV interventions.

Featured image: Image by Dean Moriarty from Pixabay.